Winy Maas colleague Šimon Knettig: We try to bring as many people together as possible to solve global problems

5/12/2022

You come to the Faculty of Architecture of the CTU as a teacher, but you started your career as an architect here. How do you remember your undergraduate studies?

I started with Eduard Schleger and it was great that the first designs were already concerned with sustainability. Then I designed coliving, an art community in Holešovice, at Stempel-Beneš studio. We worked with architects from Delft, which influenced me in my future direction. I did my bachelor's project under the supervision of Roman Koucký. I chose a personal topic, a primary art school. I myself attended the elementary school early and often, played the violin, attended art classes and the dulcimer band. It is a difficult subject because each branch has different requirements, both acoustic and dimensional.

Right after that I wanted to go to Delft for Erasmus, but because of the covid my trip had to be postponed. In the end I evaluate it positively, in the first year of the master the courses are put together in an intensive urban planning block. I learned a lot and started thinking about architecture at different scales. When I went to Delft, I spent my first semester at The Why Factory, which contributed to me finally finishing my studies in the Netherlands.

What was the difference between studying in Prague and Delft?

The technical education at the FA CTU is very intensive, I was able to think about details better than my classmates. But what is missing is the ability to think conceptually, to have a story behind a design and to be able to sell it.

In Delft, they can overlook many technical details in the evaluation because there is much more collaboration between disciplines. Here, the architect is more likely to be expected to carve out innovative solutions at the mercy of other specialists. Czech education also focuses a lot on standards. The university environment should rather look to see if standards are even relevant and look for new approaches. We should be market drivers, offering new visions and ideas where manufacturers can take their products next. Yet it is the other way around. We are waiting for companies to come up with a new idea and for architects to try and combine it into a building to make it work.

Kind of a big lego.

We are not designers of pieces and we are just looking for what to make out of ready-made pieces of materials and technologies.

What were your beginnings in Delft?

The university is located in an old building with glass halls for workshops and The Why Factory. Winy designed a huge orange staircase that acts as a grandstand for public events. The combination of openness and the original historic building makes the space rich, with overlaps and different levels. It is not a modernist open-space, but at the same time you can interact with others and be inspired by, for example, a lecture you happen to pass by.

The Why Factory is also a very specific format working with a vision of extreme collaboration. Students are expected to organize themselves into sub-groups. The work always revolves around global issues such as climate change or housing shortages. We have addressed the issue of prefabrication, which could be very beneficial, but its greater application has so far always ended up creating a boring environment lacking diversity.

Your project was called Pixel Planet?

The pixel from the graphic served as inspiration. A picture in a newspaper consists of printed dots that are all the same and uninteresting on their own, but you create richness by stacking them and making them very dense. Moreover, we evaluate the vision of The Why Factory based on concrete data. For example, one of the parameters was the area of green terraces. Therefore, you cannot do without programming, which allows you to generate forms faster than manual modeling and also collect valuable data. We use Grasshopper for this, which is a graphical programming language that is also friendly for architects. We then test the principles to extremes. So we tried to create the whole city as one structure.

Have you had the opportunity to work on real assignments in the Netherlands?

It was very fortunate that I could find some work in the field. A student can usually only be employed as an intern and is expected to be present at least 4 days a week. Thus, young architects gain work experience in the one-year gap between their bachelor and master studies. Almost no one works while going to school.

I worked with a young studio from The Hague, focusing on smaller buildings and interiors. There are visionary studios in the Netherlands that push the boundaries to extremes (like MVRDV, OMA, Mecanoo and others). But at the same time, the Dutch are a conservative nation with a fondness for traditional brick architecture. So even a new residential neighbourhood can have a 1930s character. The guys in the studio tried to push perceptions and open up new possibilities. It was sometimes difficult to communicate with the clients and convince them.

Are you now fully dedicated to teaching in Prague?

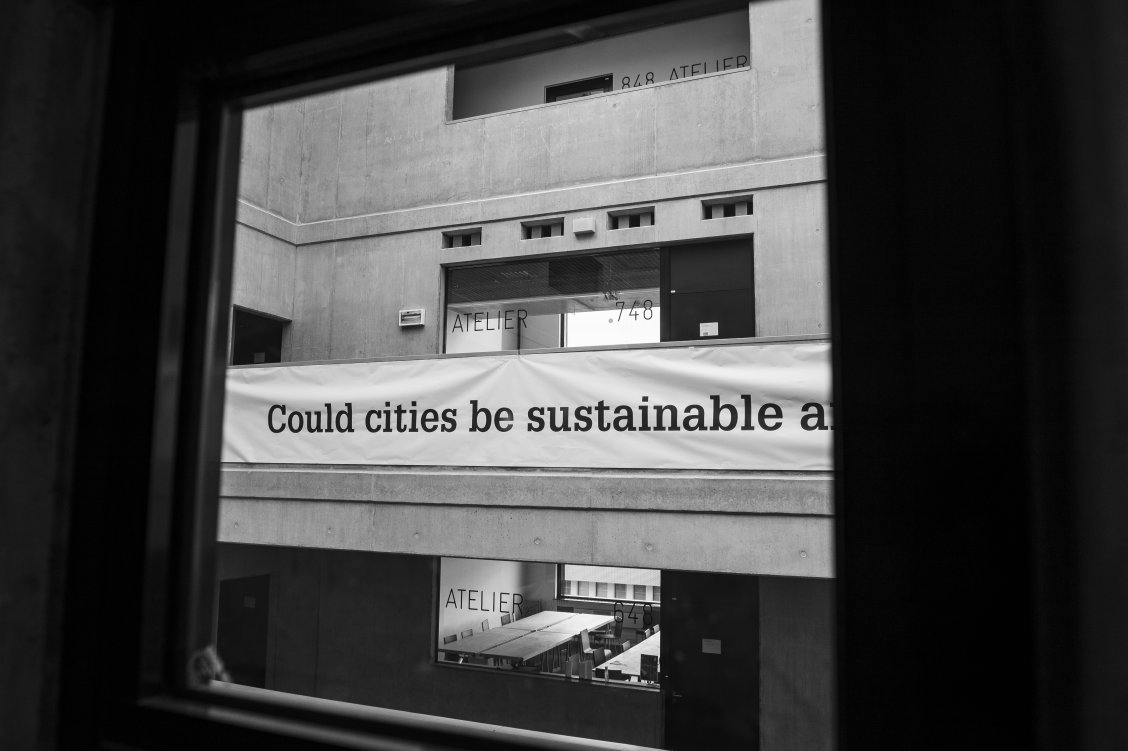

Yes, we started intensively and after the first two weeks we hung huge posters in the faculty atrium with sometimes controversial questions about what the cities of the future could look like. There are a lot of serious problems, and we should address them immediately, but we do not want to be pessimistic. On the contrary, we try to awaken enthusiasm for finding new ways and bring as many people together as possible. That is why we are also using questions in the first exhibition to involve the whole faculty and eventually the public in the discussion.

And what do you do in particular? Visionary projects can slip into superficial or familiar solutions.

This is always a problem, at some stage in the research we need to limit the number of constraints we apply to the topic. We need to get away from gravity, for example. Because with this freedom we can explore the full potential of the idea. We then take the ideas and think about how they could be applied in today's world or in the near future. Winy uses the same format in MVRDV. Unless an extreme scenario presents itself, it is awfully hard to convince clients that the topic is even worth exploring and funding. For example, MVRDV started very early on with photovoltaics, an insignificant toy technology just twenty years ago. Today, almost everyone wants to put photovoltaic panels on their roof.

We are looking for principles in the bio-world that we are not yet using and can bring us value. In the first weeks of the semester, students came up with provocative questions like, "Can we build a new Atlantis, a city underwater?"- referring to the threat to cities from sea level rise. They were concerned with food production and the self-sufficiency of metropolises. They explored bioluminescent materials and ways to make the city shine only when we really need it. They have always worked out the vision at all scales - from the room to the impact on the planet.

We are also inspired by the survival kit of travellers. When you go on a wilderness expedition, you find that every extra ounce is worth a lot and you look for things that have more than one use. That is a principle you can apply to architecture. But what defines a university? And what things in our lives are extra and get in the way like useless gear in the rainforest?

The studio will be open all year round, what awaits you in the summer semester?

Next semester, The Why Factory research will focus on the Czech Republic, a topic we dare not open without detailed research. We are contacting institutions and interesting personalities, collecting data from cities.

Is it difficult not to impose your personal worldview on students?

We teach them the methodology to be systematic and to draw conclusions that are transferable and applicable. Then we give them feedback and look for what is most interesting in what they have found. Winy has decades of experience and know-how behind it, which they are trying to pass on. But that does not mean that a student cannot come up with a new idea. That is also why experts like to work with students. You cannot always be on the lookout for new trends, and the youngest generation tends to pick up new knowledge automatically. We want to create a desire in students to have their careers look like this. Collaborative experiences with controversial visions that can lead to new solutions that our planet needs.

Interview led by Pavel Fuchs, photos by Štěpán Hon